Remembering An Army Dad on Veterans Day

It’s been 42 years since my father died. He was a career Army officer who was serving in Vietnam when the end came. Over the years it has evolved that it is this day — Veterans Day — when I pause and consciously spend hours remembering him and all that he meant to me. In 2011 I made a video:

Philip Doyle Sellers | 1928-1972 Colonel, US Army Corps of Engineers

My father was serving in Vietnam in 1972 when the end came. It’s now 40 years later and I still have dreams about him. The dreams are always the same — I’m trying to please him, and he’s not satisfied. That was the essence of a complicated relationship that shaped me more than any other influence in my lfe. I still haven’t sorted out that relationship — I wonder if I ever will?  In my earliest clear memory of him, I’m a five year old in Washington DC and he’s standing on the front steps of our apartment, spinning a shiny new football on his finger — shiny because it was still wrapped in cellophane, fresh from Sears. He’s smiling and young and happy, the sun is shining, there’s a crispness in the air, leaves are blowing, life is good and he is the pillar of my life.

In my earliest clear memory of him, I’m a five year old in Washington DC and he’s standing on the front steps of our apartment, spinning a shiny new football on his finger — shiny because it was still wrapped in cellophane, fresh from Sears. He’s smiling and young and happy, the sun is shining, there’s a crispness in the air, leaves are blowing, life is good and he is the pillar of my life.

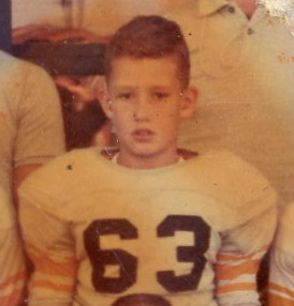

Football was his idea of how to grow a boy into a man — a test of spirit and will and leadership and poise. He’d played football in high school in Greenville, Alabama, and in college, and there was no question about it — his son was going to play football too. And baseball, which he had also played. And be damned good at it or there would be hell to pay. At the time of that first memory, he was thirty years old, a Captain in the Army, his future stretching out brightly before him. I’ll always treasure that memory because he seemed truly at peace then. Life was an opportunity, not a burden; disappointments were at bay, the future was golden.

That period of happiness was all too brief. Four years later, when I was nine and we were living in Houston where the Army had sent him on assignment as an ROTC instructor at Rice University, my whole world changed on a Sunday afternoon. The day was September 16, 1962, and George Blanda, Billy Cannon, and the Houston Oilers were on TV playing the Boston Patriots, a game they would lose 34-21. In the second half of the game I became aware of a heated, liquor-fueled argument between my Dad and my Mom in the kitchen — I’ll never forget the instant feeling of fear and uncertainty that suddenly came over me. Everything changed. I’m sure their turmoil didn’t really start on that day . . . but my awareness of it did, and for me that day stands until now as the divide between feeling happy and secure — and feeling scared and living in dread of when the next quarrel would erupt. I would later come to realize he felt his dreams were slipping away from him — that he feared that the Army, to whom he had pledged his life, didn’t appreciate him. He would always be outside the inner circle, looking in. This ate away at him.

He was truly a “man’s man” — principled, forthright, courageous when courage was required. But he was controversial, hardheaded, not “political” enough, and (the thing that fed his insecurity the most) not a West Pointer. His career, he felt, was doomed and he was going nowhere. It tormented him, and would continue to do so even after he received assignments that clearly signaled that he was not the fading officer outcast that he took himself to be. No matter how much he progressed within the Army — it wasn’t enough. In the end, he was a full Colonel, and seemed on track to make General — yet it wasn’t enough.

He loved my mother — there was never any doubt about it. And he loved me, and my sister Valerie. The problem wasn’t lack of love — in some way, it was too much of it, or too much intensity. For a strong man, he was deeply needful in certain ways. Something was missing for him — he was searching for something that he couldn’t quite find, aching for something that he couldn’t quite get, and somehow that lack passed through him and became transformed into, in my case, a blinding, critical focus on my every move that was like living in a searchlight beam. Athletics were the proving ground of character for him, and I had better measure up or else . . . . – but academics were equally important. He didn’t approach academics with passion like he did sports — he just laid down the law — nothing below a “B”, or I would have to quit whatever sport I was playing until I brought my grades up. I never dropped below a B in anything so it never became an issue.

At Rice, he seemed at his best when he was with the young men of his ROTC unit. He drilled them, trained them, and taught them. He also coached the Rice University rifle team, and would take me to the range for the practices where I learned to shoot a small bore .22 rifle at targets 50 feet away that were the size of the bottom of a coffee cup, with a bullseye the size of a .22 round. The guys on the team all seemed to look up to him, as did his ROTC cadets. I could see it in their eyes — and could see something in him when he was with them that helped me understand what he was searching for, and what he needed and couldn’t get from us, his family.

He worked hard at my indoctrination into the manly rewards of football when we were at Rice — he got Rice Owl season tickets and we never missed a game; he coached the “F.U.N. Football” (Football United National) team that I played on, the Sutton Elementary Orioles, and he identified a role model for me — Bob Johnston, right tackle of the Rice Owls, who would be all Southwest Conference and, more importantly, go on to win a Rhodes Scholarship. Johnston, my Dad told me, was the person I should emulate. He was determined that I would go to college on a football scholarship; that I would have excellent academics; and that I would become a Rhodes Scholar. That was the destiny I must aspire to — that was the future that would make a man out of me, and anything less would be a disappointment to him. That was the future he drilled into me.

And “drill” is precisely the right word. His own mix of anger and mysterious frustration with his own life manifested itself in a drill-Sergeant approach to his son. He was in my face day in, day out, for years. I could never fully please him — and no success was really a success in my mind unless I could somehow please him, so my successes weren’t celebrated as successes by either of us. And so my inner life evolved into a never-ending quest to please him, to live up to his expectations, and not let him down. If I came up short, I would hear about it — lengthy, eloquent monologues about the need for duty and honor and responsibility and the unacceptability of laziness and lack of focus and lack of will. His words ebbed and flowed and enveloping me — he could go on for 45 minutes without a break, circling the topic and squeezing every drop of meaning out of it.

But as ready as he was to criticize me, he was there to defend me too. Once, while in Houston, I hit what should have been an easy double off the centerfield fence in Little League, but the ball bounded off the wooden fence so hard, right into the hands of the center fielder, than he was able to wheel and fire it into second so that by the time I reached second, the second baseman was standing there in front of the bad with the ball ready to tag me. Instead of sliding, I just ran into him, more like a play at the plate, and he bobbled the ball and I was safe. Someone in the stands had something unkind to say about me running into the second baseman — and the next thing I knew there was a melee in the stands. My Dad stood up for me that time — and to his credit, although there was some pushing and shoving, he didn’t let his anger boil over into what could have been a tragic incident. But he didn’t let anyone get away with criticizing me–he was the one who could do that, no one else.

In a way, he was that archetypal “Little League Dad” who become obsessed with a son who has the chance to achieve what the Dad couldn’t — but only to a point. He went to every game — football, baseball, and eventual basketball — and watched me like a hawk. No matter where the play was, his eyes were on me, and there would be a critique when it was over. But unlike that archetypal Little League Dad, he wasn’t obsessed with winning. It wasn’t about that. It was about putting forward an all-out, focused effort. He never criticized mistakes as long as the mistake had been made at “full speed.” If I dropped a pass or made a throwing error or failed to come up with a timely hit to win the game – he would never come down on me for that. But if I failed to put out effort; if my attention wandered; if I showed even a hint of laziness or lack of focus, he was all over me.

His most memorable dressing down of me came in my senior year of high school. We were living in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The year prior he had completed a prestigious assignment to the Army War College in Carlisle — an assignment that signaled he was being considered as a potential General officer– and this year he was studying Vietnamese in Washington DC two hours away, commuting back and forth to Carlisle on weekends, as he prepared for an assignment to Vietnam as a Province Senior Advisor, another prestigious assignment that meant he had not maxed out his military career yet. He had been promoted to full colonel, a rank which he had never expected to make — and yet now that he had made it, rather than being satisfied with what he had achieved, he agonized over whether this was the end, or whether he could make it to General, something he would never have dreamed of as a young man but which now became an obsession.

That year, I was a two-way starter — wide receiver and defensive end — and so, when we were on offense and the play went to the other side, I was essentially a minor decoy and would tend to ease off the throttle conserving energy. But he would have none of it . . . my job was to race down the field and “find somebody to hit” — block whomever I could find and “don’t slack off”. I could hear him in the stands, and feel his binoculars on me every single play of every single game.

Midway through that season, I broke a rib and as a result was relieved of my defensive end duties. Strapped up with a makeshift pad over the broken rib, I would only have to play offense. This meant that I no longer had any issues about conserving energy, and in the first game where I only had to play offense, I played what I thought was the perfect game–not in terms of the number of receptions, or touchdowns, or even whether the team won or lost. All of these elements of the game have faded from memory, but what remains is the fact that I was absolutely confident that I had gone 100% all-out on every single play from scrimmage; I had raced downfield on every play, finding a player to block on each play, never letting up, never giving my Dad a single thing to complain about. I remember showering, gathering up my books and belongings and heading out of the locker room with, for the first time, a sense of certainty that he couldn’t find fault with my performance.

I reached the car. He was sitting behind the wheel, smoking a cigarette. My mom was in the seat beside him. I climbed in the back and could tell immediately that they had been arguing. Crap, I thought. What now? I was quiet. They were quiet. He made no move to drive the car. My mom said something about “good game, honey” and drew a cold stare from him. Then he turned to me proceeded to give me what turned into a twenty minute tongue lashing. Why?

Well, I was right in my estimation that he would not be able to find fault with my performance during the game. The problem wasn’t what happened during the game — it was what happened prior to it. During the national anthem, it turned out, I had not been standing at proper attention, and I had fidgeted, and been disrespectful, and that was totally unacceptable. Yes, sir. Yes, sir. I understand, sir.

Inwardly I raged against him and hated his constant demands on me . . . yet I never stopped wanting and needing to please him, and in some way that need that he had instilled in me, and the discipline that came with it, transferred to the rest of my life and fueled a drive for success and achievement during high school, college, and beyond. He left for Vietnam on his second tour of duty in the spring of that year, my senior year, to serve as Province Senior Advisor to the provincial governor of Ninh Thuan province along the coast in central South Vietnam. It was an 18 month tour instead of the usual 12 months, with my mother and sister being able to live at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, and Dad able to travel out once ever six weeks for a five day visit with them. Ninh Thuan province was in Military Region Two, and my father served under John Vann, a controversial Macarthur like figure who had come back from retirement, and whom he admired greatly.

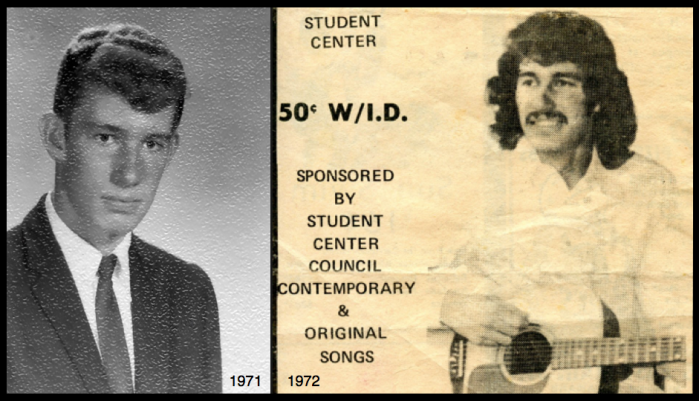

He went to Vietnam, and I went on to college–on a football scholarship as he’d always said I would–to the University of Delaware. Free of his constant presence and pressure, and with the help of a decidedly progressive girlfriend and a roommate who would go on to be a successful Nashville songwriter, I discovered other aspects of my personality. I learned to play guitar, and write songs, playing in coffee houses and campus events, taking a kind of subversive pleasure in being a jock on the one hand, and an artist on the other. I let my hair grow out to the limits of what the football coaches would allow; I grew a mustache; I finally had the mini-rebellion against authority and orthodoxy that he would never have allowed.  At Christmas that freshman year, our family met in Hawaii, and I was nervous — deeply so — at the reception my ‘new look’ would elicit from my father. The transformation since he’d left 8 months earlier was profound, and I knew it would be difficult for him – but I was determined to stand my ground. There would be no dragging me off to get my hair cut. I was beyond that, and I was ready to stand up to him.

At Christmas that freshman year, our family met in Hawaii, and I was nervous — deeply so — at the reception my ‘new look’ would elicit from my father. The transformation since he’d left 8 months earlier was profound, and I knew it would be difficult for him – but I was determined to stand my ground. There would be no dragging me off to get my hair cut. I was beyond that, and I was ready to stand up to him.

I’ll never forget — it was 5 am when they arrived the hotel, the three of them — Dad, Mom, and my sister Valerie. They knocked on the door and I opened it — he took one look and said, ‘Oh my God’, and I thought — here we go. “We’ll talk about that tomorrow,” he said — “that” being the hair that tumbled to my collar and the mustache that, with the hair, affirmed my evolving notion of myself as an artist, not “just a jock”.

I waited for the confrontation — but it never happened. At first I thought he was just lying in wait, choosing his moment, as one day passed, and another, and he made no mention of the hair. I could tell, too, that he was trying in other ways. My mother had made it clear that she’d had just about enough and, with my sister about to graduate from high school, it was time for the turmoil to stop, or she would be gone when the nest was empty. Ever since that day in Houston when I’d first become aware of their strife, he had always been the aggressor, the instigator — my mother the victim. But that Christmas, in Hawaii, something had changed. He was trying in ways that I’d never seen. And now, just when he was trying the hardest — she was the tough one, the unforgiving one, the one who would seize upon any bit of backsliding and make him pay for it.

Their relationship had turned, and the irony was that just at the moment when he seemed to have gotten the message and was fighting to keep his demons in check, her own demons were coming out and she had become an unforgiving presence–understandably so, given what she’d been through. But I found myself rooting for him, hoping he could hang in their and transform himself as he was trying to do. My Christmas present from him was, as it turned out, a guitar he’d bought me in the Philippines and brought with him. On Christmas day, as we sat on the balcony of the hotel at sunset and my mom and sister were inside getting ready to go to dinner, he asked me to play it for him. I played, then he said, “No – I meant play and sing. Your own songs, the ones you play when you perform.” I played, and he listened. One of the songs, Ithaka, was brand new and would become my anthem for life. I sang it for him:

On the day you start your journey, pray that the way is long

Full of hopes, full of dreams, in the cool grey light of dawn

Take a look around you, let your spirit set you free

Let your mind hold the standard, upon your odyssey

Pray that the way is long, that the summer mornings last

That the candles of your future, gently melt into your past

Something about the lyrics, and his life, and my life, caused us both to start getting choked up. There we were, the two of us, sitting on the balcony of a hotel room in Hawaii, discovering something in each other that neither of us had ever known existed. I made it through to the last verse with tears rolling down my cheeks.

And though you find the island poor, the knowledge that you’ve gained

Says that you belong to her, though somehow you’ve both changed

Now you’ve come to understand, just what the island means

It was she who sent you on your way, and answered all your dreams

So look back on your journey, think of everywhere you’ve been

Thank her for your wisdom, though you’d do it all again

And Pray that the way is long, that the summer mornings last

That the candles of your future, gently melt … into … your past.

He didn’t say anything when I was finished — he couldn’t talk, neither could it. He was not someone who cried easily or openly, but in that moment we both did. Everything about the moment was unexpected — him seeing me in a different light, and me discovering in him a capacity to feel that had been masked all these years. “I could never do that,” he said. And then: “I wish I could.”

He was trying; he was changing.

I loved him more that day than ever and for the first time really had hopes for resolution in our relationship.

But it wasn’t to be.

The next time I would see him was six months later, on the tarmac at Clark Air Base in the Philippines as he was wheeled off a flight on a stretcher, an IV hooked into his arm, unconscious, his face gaunt and his body ravaged by hepatitis that had been allowed to go on too long, and which had been deeply complicated by his drinking, which had just become worse and worse over the years, and which his 11th hour effort to reform himself had failed to control.

He would never be fully coherent after that — a destroyed liver leaves you in a fog until it takes you away — and three weeks later he would die. I was there beside him. In fact, in perhaps the final convolution of his tormented spirit, he fought against letting my mother comfort him in his final days — he was somehow too humiliated by his condition. It was only his son that he would allow to see him in his state. Lying in the hospital bed, he would suddenly and repeatedly rise up from his torpor, raging against the demise that was racing toward him. Sitting beside him — I would leap up, grab him when he did this, then massage the back of his neck and shoulders until gradually he would relax, and lose consciousness again.

This is it? I thought. Life comes down to this?

For my mom, it was a nightmare. She had stood by him through so much. They had loved each other passionately and devotedly – yet his demons had gotten between them, and she had begun to lose hope. Yet she wanted to be there for him, with him, in those final days — but somehow his pride, billowing out through the haze that enshrouded him, wouldn’t allow it. He didn’t know where he was, nor did he fully understand what was happening — but the one thing that made its way through the fog was his unwillingness to let the love of his life see him undone and incapacitated not by the enemy in Vietnam, but by the enemy within, the demons that had hounded him into final submission.

Finally death came.

During the last night a Philippine typhoon raged outside, but he was peaceful, too far gone to object to anyone or anything — and we could all be there, mother, daughter and son, to say farewell as life quietly slipped away and he finally found the peace that had eluded him in life.

He was forty-four when he died.

His service to country was what he wanted to define him — two tours of duty in Korea, two in Vietnam, a chestful of awards and ribbons. He would likely have made General had he lived — yet he died convinced that such a promotion would never happen. We’ll never know, of course, what might have been.

What I do know is that he loved his country deeply, and he loved his family — but more than this, the thing that gave him the greatest satisfaction above all else and which provided the only feelings of inner peace that I ever witnessed from him — was to be respected as a leader of men. He was happier in Korea and Vietnam than he ever was at home–you could see it in his eyes in the pictures of him, you could feel it in the letters he wrote, the audio tapes he sent home to us, the wistful way he talked about being in the “combat zone” when he was back stateside.

Being a leader of men was what his nature called out for; that was what he would strive for consistently and without hesitation throughout his life; and that is how he would want to be remembered.

Father? Yes.

Husband? Yes.

But . . . leader of men?

Hell yes.

He loved serving his country, and in a complicated and messy way, died for it.

Forty years on, I miss you, Dad. I’ll never forget our moment on that balcony, our last moment together.

I wish there could have been more but at least we had that.

Year of the Spy Book Trailer

Above is the Year of the Spy Book Trailer — for my upcoming non-fiction book about espionage upheavals on the streets of Moscow in 1985.

Below is a “trailer” showcasing the writing and video services I provide to clients.

Michael Sellers — Writing and Video Services

My eBook — Just released Dec 5, 2012

EBook You don't need a Kindle or iPad -- Download Adobe Digital Editions for Free, then read the .mobi (Kindle Format) or .epub (Nook, iPad Format) digital book on your computer. Or order the PDF which is formatted exactly like the print book.Recent Posts

- Arsha Sellers — Today I’m One Big Step Closer to Becoming a Real Forever Dad

- Meet Abby Sellers and Arshavin Sellers — My Wife, My Son, My Inspiration Every Day

- What the Mueller Report Actually Says

- Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

- America the Beautiful? You Mean America the Pitiful. I Am Ashamed