Few Americans Realize That the US has Deep Historical Connections to Typhoon Ravaged Philippine Islands of Leyte, Samar

As the tragedy wrought by Typhoon Hainan (Philippine designation Yolanda) unfolds in agonizing slow motion, Americans find themselves looking at a region in the Philippines that bears a deep historical connection to America — yet it is a connection that is little known to the general population in the US. To Filipinos or students of Philippine-American history, the following will be very familiar. To Americans who have no Philippine connection, much of it is likely to be news — and it is for these Americans that I offer the following account of our nation’s connection to the islands of Leyte and Samar, and their inhabitants whose history has been intertwined with our own.

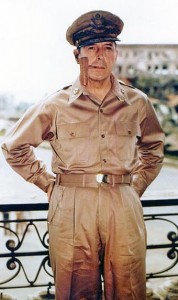

General Douglas MacArthur and the Leyte Landings

When World War II broke out for America on December 7, 1941 with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines was an American colony, acquired by America as part of the outcome of the Spanish-American War of 1898. The Japanese bombed Clark Air Base in the Philippines within hours of bombing Pearl Harbor, and quickly invaded the Philippines and took control of them. General Douglas MacArthur, who had been brought out of retirement to head USAFE — the mostly Philippine Army — was ordered by President Franklin Roosevelt to leave the Philippines. On March 11, 1942, Macarthur boarded a gun ship in the Philippines and ran the Japanese blockade, eventually making it to Australia where he told reporters: “I came through and I shall return.” On April 9, 1942, more than 10,000 American troops and many more Filipinos surrendered to the Japanese.

When World War II broke out for America on December 7, 1941 with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines was an American colony, acquired by America as part of the outcome of the Spanish-American War of 1898. The Japanese bombed Clark Air Base in the Philippines within hours of bombing Pearl Harbor, and quickly invaded the Philippines and took control of them. General Douglas MacArthur, who had been brought out of retirement to head USAFE — the mostly Philippine Army — was ordered by President Franklin Roosevelt to leave the Philippines. On March 11, 1942, Macarthur boarded a gun ship in the Philippines and ran the Japanese blockade, eventually making it to Australia where he told reporters: “I came through and I shall return.” On April 9, 1942, more than 10,000 American troops and many more Filipinos surrendered to the Japanese.

Macarthur’s promise to return became a rallying cry for the Japanese-occupied Philippines. Philippine and American guerillas hid in the jungles and mountains, monitoring the Japanese presence and preparing for MacArthur’s eventual return. Meanwhile, as the war progressed, the American leadership made the decision to attack Japan directly rather than battle them in the Philippines. MacArthur vigorously pushed President Roosevelt and Pacific Commander Chester Nimitz to send forces to the Philippines, eventually prevailing — the US would, in fact, attempt to retake the Philippines from the Japanese.

It was against this background that on October 20, 1944, the U.S. 6th Army stormed the beaches of Leyte. Then, famously, MacArthur arrived in the company of Philippine President in exile Sergio Osmena, Philppine Genera Carlos P. Romulo, as well as the U.S. Seventh Fleet commander Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid on October 20, 1944. MacArthur and the others waded ashore at Red Beach, in Barangay Candahug, Palo, Leyte, 5 kilometers south of Tacloban City. The landings marked the beginning of the push for the liberation of the Philippines from Japanese control.

Macarthur famously made a radio address to the Filipino people from the beachhead in Leyte. To our 2013 ears it may sound a bit “over the top” — but in the context of the moment to a country that had been occupied and under Japanese rule for more than two years, Macarthur’s message, delivered with great and obviously heartfelt emotion, truly resonated:

TO THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES:

I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil — soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come, dedicated and committed, to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring, upon a foundation of indestructible, strength, the liberties of your people.

At my side is your President, Sergio Osmena, worthy successor of that great patriot, Manuel Quezon, with members of his cabinet. The seat of your government is now therefore firmly re- established on Philippine soil.

The hour of your redemption is here. Your patriots have demonstrated an unswerving and resolute devotion to the principles of freedom that challenges the best that is written on the pages of human history. I now call upon your supreme effort that the enemy may know from the temper of an aroused and outraged people within that he has a force there to contend with no less violent than is the force committed from without.

Rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on. As the lines of battle roll forward to bring you within the zone of operations, rise and strike. Strike at every favorable opportunity. For your homes and hearths, strike! For future generations of your sons and daughters, strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike! Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of divine God points the way. Follow in His Name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory!

Douglas MacArthur

The Filipino guerrillas dynamited key bridges; they harassed enemy patrols; and they sabotaged supply and ammunition depots. Information on enemy troop movements and dispositions sent from guerrilla outposts to immediately to Sixth Army. In all, more than 300,000 Filipino guerrillas worked side by side with the Americans until the liberation was complete, and the Japanese were expelled.

Today, the Leyte Landing Memorial is located on the same site in Palo, south of Tacloban, where MacArthur and Osmena waded ashore. The memorial consists of bronze statues of the party wading ashore, situated in a manmade pool.

Samar 1901 — The Balangiga Uprising

The other major historic event in Philippine-American history that took place along the track of typhoon Hainan/Yolanda is a more complicated one — yet no less significant, particularly from the Philippine point of view. The Balangiga Uprising, also known as the Balangiga Massacre, is the story of how a Philippine town rose up against an American occupying force during the Philippine-American War (yes, there was a Philippine-American War and it was a lot like Vietnam or Iraq) and expelled the Americans.

How did America end up in a war with the Philippines?

Very briefly (and with apologies to historians for the possible oversimplification of a complicated scenario), in 1898 America fought the Spanish-American War on two fronts — the Spanish colony of Cuba, and the Spanish colony of the Philippines. America won, and although the US had claimed at the outset that it was fighting the war essentially for moral reasons (Spanish mistreatment of its colonies) and had no territorial ambitions — by the time the treaty talks took place in December 1898, the US government had decided that it wanted to acquire the Philippines as a colony. It did so. Filipino insurrectos who had been fighting the Spanish for may years, and who had made common cause with the Americans against the Spanish, helping the Americans with the siege of Manila, felt betrayed. In February 1899 war broke out. There was a brief period of conventional warfare, and a much longer period of guerrilla warfare in which the Americans were harrassed by guerrillas (sound familiar?) based in the mountains and jungles and supported by the townspeople.

Two years later, in August 1901, an American contingent landed in Balangiga on the coast of Samar with orders to implement an aggressive policy of food and property destruction and to otherwise take measures to choke off supplies to the insurgents in the surrounding jungles and mountains.

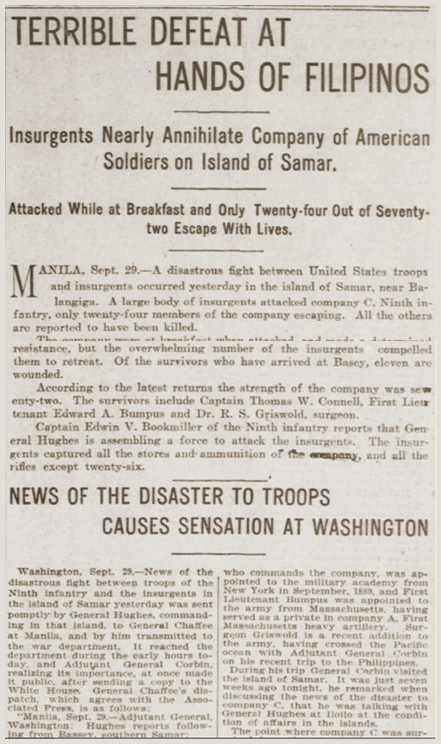

Six weeks later, on September 28, 1901, the townspeople in coordination with the rebels rose up and killed 48 of the 74 Americans. Here is how the New York Times covered the story:

The stunning defeat, which was labeled by the newspapers of the day as America’s worst military defeat “since Little Big Horn”, caused a sensation in the United States and resulted in a campaign of retribution which proceeded under US General Jacob Smith, who famously ordered Colonel Littleton Waller to turn Samar into a “howling wilderness” – earning him the nickname “Howling” Smith, and ultimately earning him a court martial. In his court martial, it was established that Smith told Waller: “I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better you will please me. I want persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States,” There is a great deal of dispute about how many Filipinos the Americans killed. Responsible scholarship places the number of Filipinos killed in the campaign of retribution in the vicinity of 2,000-3,000, with many homes were burned, and towns demolished. The popular version in the Philippines–which has generally been debunked by serious scholars of both Philippine and American orientation–erroneously placed the number of those killed in the campaign of retribution far higher — in the hundreds of thousands. Regardless of what the numbers actually were, there was no denying it was an ugly affair that brought no honor to America, and was only partially rectified by the court martials and howls of outrage that would eventually emanate from the US once matters were brought to light.

As a final insult to Filipinos, during the campaign of retribution the US Army took two (and possibly 3) bells from the church in Balangiga, never returning them to the Philippines in spite of the close relationship that ensued after the fighting was over, and which continues now, more than a century later. This remains unresolved, and is a sore point between the countries. Increasingly, there are Americans calling for the bells to be returned — but it hasn’t happened. They remain at an Air Force Base in Wyoming, where it custodians steadfastly refuse to return them to the Philippines.

A Personal Post Script

The Balangiga Uprising is memorialized each year with a re-enactment in Balangiga, and Americans are welcome and treated with wonderful hospitality. I know, because I’ve been there and attended it. The atmosphere of the re-enactment has little to do with anger or hatred towards America, and everything to do with a proud assertion of Filipino honor and pride. It was an incredibly heroic decision to attack the Americans — who were armed with the highest military technology of the day — armed with nothing more than bolo knives and courage. And without going into all the details — there was reason for the attack. It was not unprovoked.

If you would like to read more, I suggest two areas of exploration. First, an article I wrote: The Balangiga Massacre: A Hero Tale, a Tragedy, and a Tantalizing Unsolved Mystery. Secondly, the definitive book on the uprising is Hang The Dogs: The True Tragic History of the Balangiga Massacre, by my good friend Bob Couttie. If you would like to read a highly partisan pro-Filipino account, The Balangiga Massacre: Getting Even.

2 Responses to Few Americans Realize That the US has Deep Historical Connections to Typhoon Ravaged Philippine Islands of Leyte, Samar

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Year of the Spy Book Trailer

Above is the Year of the Spy Book Trailer — for my upcoming non-fiction book about espionage upheavals on the streets of Moscow in 1985.

Below is a “trailer” showcasing the writing and video services I provide to clients.

Michael Sellers — Writing and Video Services

My eBook — Just released Dec 5, 2012

EBook You don't need a Kindle or iPad -- Download Adobe Digital Editions for Free, then read the .mobi (Kindle Format) or .epub (Nook, iPad Format) digital book on your computer. Or order the PDF which is formatted exactly like the print book.Recent Posts

- Arsha Sellers — Today I’m One Big Step Closer to Becoming a Real Forever Dad

- Meet Abby Sellers and Arshavin Sellers — My Wife, My Son, My Inspiration Every Day

- What the Mueller Report Actually Says

- Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

- America the Beautiful? You Mean America the Pitiful. I Am Ashamed

obviously like your website but you need to check the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I will definitely come back again.

I enjoyed your blog entry.

Please note that my picture of the MacArthur Memorial is not in the public domain and it’s use constitutes copyright infringement.

Although I am flattered that you used it, either a photo credit and/or a request to use it would have been in order.

Have a nice day and please continue with your informative blogging.