Remembering James H. Blount, an unsung hero of Philippine-American history

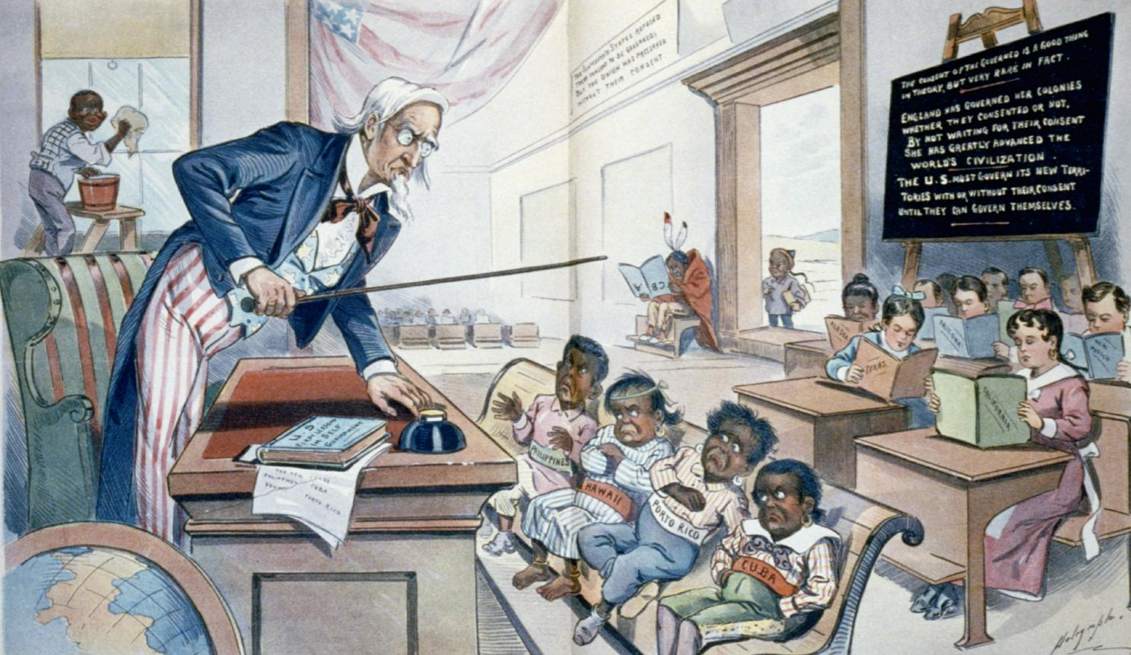

In popular culture we’ve seen this tale on the silver screen: John Dunbar in Dances With Wolves, or Jake Sully in Avatar; the American soldier who is sent to a distant land and finds himself siding with the “enemy”, who is not an enemy at all but a culture as worthy (or moreso) than America’s own. In the real world pantheon of American soldiers who have been thrust into an alien environment and seen their values transformed, James H. Blount stands out as one who contributed much, but is remembered little. Those undertaking a formal study of Philippine American History in sufficient depth to warrant seeking out “primary source” historical texts will be familiar with his work; but he has no place in the general consciousness of Americans or Filipinos. He deserves better, and since the means to make a movie about his life (oh, would I love to do that!) don’t immediately exist, I will content myself with writing an article about why he should be remembered, and hope that it finds its way into google search results in a way that helps, at least a little, in increasing awareness of Blount and his writings.

First, the good news: Blount’s Anti-Imperialist magnum opus “The American Occupation of the Philippines 1898-1912” is now available for free in eBook form. Just click on this download link and and it’s yours. If you don’t have Kindle software on your computer — that’s free too and can be downloaded here for Mac and here for PC) you can have a free copy of this very important and highly readable book.

Blount had a unique perspective. After serving in Cuba during the brief campaign of the Spanish American War, he was transferred to America’s new colony of the Philppines where he served as a military officer from 1899-1901 during the peak period of the Philippine American War, and then as an American colonial official serving as a circuit Judge from 1901-1905. Suffering from various infirmities, he returned to the US in 1905 where he became a leading voice in Anti-Imperialist Circles, giving speeches and lectures and writing articles all of which were focused on calling attention to the injustice of America’s policy toward the Philippines, culminating in 1913 with the publication of “The American Occupation of the Philippines 1898-1912”.

I first came across Blount’s opus when I was “reading in” at the State Department in preparation for assignment to the Philippines in the months after the EDSA Revolution in 1986. I found myself quite taken by Blount’s vivid, passionate, and colorful account of the ironies and hypocrisies of American Policy toward the Philippines, by one who had been tasked to implement those policies. He had a highly intense and personal way of composing his arguments. A good example comes in his introduction to “Occupation”:

This book is an attempt, by one whose intimate acquiantance with two remotely separated peopels will be denied in no quarter, to interpret each to the other. How intelligent that acquiantaince is, is of course altogether another matter, which the reader will determine for himself.

The task here undertaken is to make audible to a great free nation the voice of a weaker subject people who passionatelyy and rightly long also to be free, but whose longings have been systematically denied for the last fourteen years, sometimes ignorantly, sometimes viciously, and always cruelly, on the wholly erroneous idea that where the end is benevelot, it justifies the means, regardless of the means necessary to the end.

At a time when all our military and fiscal experts agree that having the Philippines on our hands is a grave strategic and economic mistake, fraught with peril to the nation’s prestige in the early stages of our next great war, we are keeping the Filipinos in industrial bondage through unrighteous Congressional legislation for which special interests in America are responsible, in bald repudiation of the Open Door policy, and against their helpless but universal protest, a wholly unprotected and easy prey to the first first-class Power with when we become.

Blount’s passionate and articulate attack on American policy toward the Philppines, rooted in 7 years of personal experience no just in Manila, but throughout the Philippines, did not endear him to what we now term the “mainstream” media, as the New York Times review in 1913 makes clear:

It is doubtful whether public opinion in the country will be affected much by James H. Blount’s book entitled “The American Occupation of the Philippines 1899-1912.” This criticism is not based on the fact that the author is an “anti-imperialist” and an ardent pleader for Filipino independence, but on the fact that in presenting his views he is undified, unjust, intemperate, and abusive.

Really?

Even when I first read Blount’s book, at a time when I was about to journey out to the Philippines in a similar capacity — i.e. to work side by side with the officials of Cory Aquino’s government to help re-establish democratic instituations in the aftermath of 15 years of martial law– I thought his views were anything but abusive: they were cogent, articulate, and enlightening.

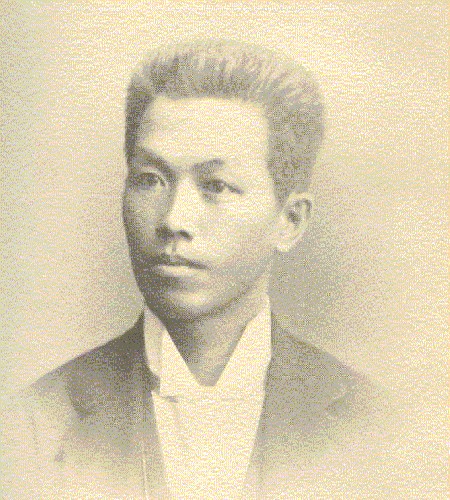

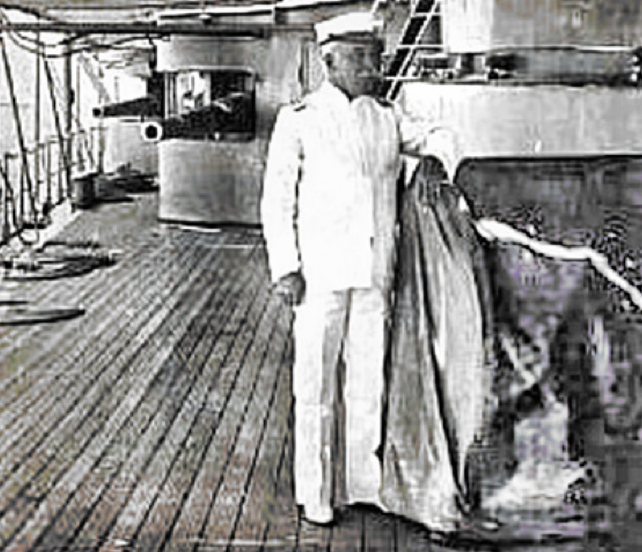

“Occupation” begins at what is arguably the beginning of America’s adventure in the Philippines — with American Ambassador Spencer Pratt in Singapore in April 1898 at the time of the outbreak of war between America and Spain. Meticulously researched and vividly re-created, Blount recounts how Pratt approached Philippine leader Emilio Aguinaldo, then exiled in Singapore, and engineered for Aguinaldo to go to Hong Kong and present himself as an ally to Admiral James Dewey, who was then preparing to sail to Manila to confront the Spanish fleet. Blount is unequivocal in stating that Pratt absolutely did promise Philppine independence to Aguinaldo, doing so without authority and with the result that soon thereafter, Pratt was separated from the consular service and forced to retire.

“Occupation” begins at what is arguably the beginning of America’s adventure in the Philippines — with American Ambassador Spencer Pratt in Singapore in April 1898 at the time of the outbreak of war between America and Spain. Meticulously researched and vividly re-created, Blount recounts how Pratt approached Philippine leader Emilio Aguinaldo, then exiled in Singapore, and engineered for Aguinaldo to go to Hong Kong and present himself as an ally to Admiral James Dewey, who was then preparing to sail to Manila to confront the Spanish fleet. Blount is unequivocal in stating that Pratt absolutely did promise Philppine independence to Aguinaldo, doing so without authority and with the result that soon thereafter, Pratt was separated from the consular service and forced to retire.

Blount then traces Aguinaldo’s dealings with three crucial Americans: Dewey, and Generals Andersen, Merrit, and Otis. Out of these four relationships comes the most reasonable and balanced account I have ever read of just how it happened that America granted independence to Spain but not the Philippines — yet gave Filipinos the clear impression that independence would indeed be forthcoming. My Filipino friends who think much about such things tend to simply believe that Dewey “lied through his teeth” to Aguinaldo, to gain the latter’s cooperation. Blount’s beat by beat explanation, coming from someone who is sympathetic to Filipino aspirations but also a good researcher and one who is aware of “the way things are” in the US Government — manages a compelling explanation for just how Dewey came to mislead Aguinaldo which has the ring of truth and reality.

One of the first points which Blount reminds us of is that Aguinaldo never met with Dewey in Hong Kong — he arrived the say after Dewey sailed, and came across from Hong Kong to the Philippines on the Mccullough, arranged by Pratt’s counterpart in Hong Kong, Consul Wildman, who like Pratt clearly led Aguinaldo to believe that Philppine independence was in the offing , as evidenced in a letter he wrote to Dewey in which he wrote:

Do not forget that the United States undertook this war for the sole purpose of relieving Cubans from the cruelties under which they were suffering, and not for the love of conquest of the hope of gain. They are actuated by precisely the same feelings for Filipinos.

General Andersen, one of the other interlocutors who would be implicated in misleading Aguinaldo, was quoted in 1900 in the Chicago Record as saying:

Every American citizen who came in contact with the Filipinos at the outset of the Spanish-American War, or any time within a few months after hostilities began, probably told those that he talked with that we intended to free them from Spanish oppression. The general expression was, “We intend to whip the Spaniards and set you free.”

One of the interesting aspects of Blount’s account is the degree to which it shed’s light on the state of Dewey’s likely knowledge, or lack of knowledge, about America’s ultimate policy toward the Philippines during the period between May 1, 1898, when he defeated the Spanish Armada in Manila Bay, and June 30th, when American ground forces finally arrived, bringing with them not only their military capacity but also news of the evolving view of the Philippines as seen by an America who had wandered into the Spanish American conflict without much thought about the Philippines–most of the focus being on Cuba.

As recently as December 1897 President McKinley had gone on record stating that war with Spain would never be fought with “forcible annexation” in mind: “That by our code of morality would be criminal.” And indeed the Teller Amendment, necessary to gain the vot in Congress necessary to authorize the war, explicitly stated that American could not take Cuba as a colony, but would instead grant independence. The Americans first present n the Philippines seem to have assumed that the Teller Amendment and statements of the “criminality” of forced annexation would apply — and thus freedom would be granted to the Philippines, same as Cuba.

Blount doesn’t give Dewey a “pass” on having contributed to the deception – rather he just provides the kind of intelligent context necessary to make the whole sorry episode understandable to anyone who cares to try and imagine how it actually went down.

Chapter after chapter, with great verve and not a little caustic wit, Blount recounts each of the beats of America’s historic involvement in the Philippines. He buttresses his own observations with extended quotations from the subsequent congressional testimony of Dewey and others, and puts a microsope onto the performance of a series of American military leaders, and then governors general, in the Philippines.

In the end, Blount throws his backing to the Mcall Resolution, which was then a proposal popular among anti-imperialists for an early grant of independence to the Philippines, coupled with guarantees that the Philippines would be “neutral” in a manner analagous to Switzerland (this to counter the argument that if America left, another great Power would move in and take over).

The McCall Resolution read:

JOINT RESOLUTION

declaring the purpose of the United States to recognize the independence of the Filipino people as soon as a stable government can be established, and requesting the President to open negotiations for the neutralization of the PHilippine Islands.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America: in Congress assembled:

That in accordance with the prinicples upon which this overnment is founded and which were again asseterd by it at the outbreak of the war with Spain, the United States delares that hte Filipino people of right ought to be free and independent.and announces its purpose to recognize their independene as soon as a stable government, republican in form, can be established by them and thereupon to transfer to such goeverment all its rigths in the Philippine Island s upon terms which shall be reasonable and just, and to leave soverignty and ctonrol of their country to the Fililpino people.

Resolved, That the Preisdent of the United States be, and he hereby is, requested to open negotiations with such foreign Powers as in his opinon would be parties to the compact for the neutralization fo the PHilippine Islands by international agreement.

That was 1913. In the end, it was 1946 before the Philippines would be released from the ‘claws of the eagle’ — but it is worth remembering that there were good Americans like Blount who “got it” long before the American government finally “let go” ….. they are worth remembering, as Blount is, for taking a stand that was less than popular, but which was right and consistent with the veryp rinciples on which America had been founded, and which its leaders seemed to forget.

It’s a great book and it’s free.

4 Responses to Remembering James H. Blount, an unsung hero of Philippine-American history

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Year of the Spy Book Trailer

Above is the Year of the Spy Book Trailer — for my upcoming non-fiction book about espionage upheavals on the streets of Moscow in 1985.

Below is a “trailer” showcasing the writing and video services I provide to clients.

Michael Sellers — Writing and Video Services

My eBook — Just released Dec 5, 2012

EBook You don't need a Kindle or iPad -- Download Adobe Digital Editions for Free, then read the .mobi (Kindle Format) or .epub (Nook, iPad Format) digital book on your computer. Or order the PDF which is formatted exactly like the print book.Recent Posts

- Arsha Sellers — Today I’m One Big Step Closer to Becoming a Real Forever Dad

- Meet Abby Sellers and Arshavin Sellers — My Wife, My Son, My Inspiration Every Day

- What the Mueller Report Actually Says

- Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

- America the Beautiful? You Mean America the Pitiful. I Am Ashamed

Nice to see this post on the centennial of the death of James H. Blount, Jr.; today is October 18, 2018.

If you make a movie about him, I’d like to help, though I’m afraid that no one is around today who knew him.

James Blount Griffin

My husband and I are currently writing a family history book and have drawn extensively from Judge Blount’s work. The Philippine-American War remains largely undiscussed in our Philippine schools, and we are grateful for the e-accessibility of this brave and detailed narrative. Hope more people get to read his book.

Miguel and Jean Paterno

I’m interested in knowing what church-if any-Blount, Jr. might have called his. So many in the anti-imperialist cause we’re liberal Christians.

I, who long ago published an article about his father, Congressman James H. Blount, Sr., in the Atlanta Historical Society’s journal, enjoyed very much this article about my Grandmother’s first cousin, Blount, Jr. I strongly suspect his father’s anti-imperialism influenced him. Blount, Sr was sent to Hawaii by President Cleveland to investigate after Americans overthrew its Queen. He recommended Hawaii not be annexed by the U.S. because its natives opposed it. Blount, Jr. published an interesting article in the “North American Review” in 1907 about independence for the Philippines.